In this post Tara reflects on both her time as Writer-In-Residence and the difficulty of carving out time for writing. She also generously shares an early draft of a new short story along with some of the questions that have come up during the early editing process.

Today is my penultimate session as writer-in-residence at the Preston Park Recovery Centre. I’m writing at a table in the café at the back of this roomy, light-filled Victorian villa while through the window, blossom falls diagonally from cherry trees in the lovely garden – it’s another of these freak warm days. People wander in for tea or coffee, and say hello. There’s a real sense of safety, creativity and camaraderie here. I’ve been made to feel very welcome, by staff and service users. I’ll miss the place and the people when I go.

I’m trying to squeeze in an hour of writing before the day gets busy. My writing time is punctuated by conversations with service users. We don’t just talk about writing though, we talk about life, football, the news, astronomy, history and sometimes people let me read their writing, and this is a delight and a privilege. I offer writing support, encouragement, feedback or I just listen. I know how important it is as a writer, even occasionally, to have a witness, a listening audience, however small.

I also set aside an afternoon at home each week to focus on the writing I’ve started during this project. Because of the residency I’ve felt able to give myself ‘permission’ to take this time out of my normal busy week. Alongside the demands of lone parenthood and a part-time job I’ve been working on a novel for the last few years. I find it hard to prioritise my own writing, and when I do find time, the focus is often on product, on crossing things off lists: how many more chapters have I done? What’s my word count now? Have I got that next scene redrafted? Does it need more editing? Is it good enough?

In Bird by Bird, Ann Lamott says:

“Perfectionism is a mean, frozen form of idealism while messes are the artist’s true friend.”

I tend to be a bit of a perfectionist. So even though the unmapped, clumsy early stages of the creative process, where messes are made, are the life blood of creativity, those stages can trigger intense anxiety and frustration for me. I think a lot of writers feel this way.

The unique aspect of the Creative Future residency is that it is not prescriptive, it is simply free space and time to create, to reflect, to write, to make messes. I feel incredibly fortunate to have been given this. This freedom from the pressure of product takes the anxiety out of exploring new territory. Plus, it’s been a refreshing relief to work on some new pieces away from the novel.

Initially I was dizzy, knocked sideways by a rush and frenzy of ideas jostling for attention and confused about what to focus on first. So I deprived myself the capacity to edit digitally and exorcised them all on a new second-hand type writer, dashing out pages of shambolic first drafts and every wild idea. Finally I settled and I’ve been chipping away at two short stories. I’ve included below an excerpt of one of them.

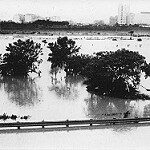

Earlier this year some of my family were directly affected by the severe floods in the north. Inspired by this, and the theme for the Creative Future Literary Award this year, ‘A Sea Change’, I started imagining a total physical transformation of environment and what that might trigger emotionally and psychologically for the characters involved.

I love The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey Eugenides and A Rose for Emily by William Faulkner is one of my favourite short stories. Both are narrated in first person plural. I thought the collective ‘we’ would suit my story. I like the odd, mythical quality of the collective voice, with its originals in the Greek Chorus. It seems to fit a watery environment which blurs individuality, and also feels right for an epic event which is experienced collectively – which both shocks and unites the community.

As I work on the story, certain concerns begin to surface.

- The collective ‘we’ has an appealing quality but it can limit the narrative – it can highlight the constructed nature of the text, taking the reader out of the story, and I’d like to avoid that if I can.

- I’m wondering how I can make the story arc in a way that is emotionally compelling and convincing when there is no focus on individual character. My stories are always character driven and zoom in very closely on the psychology of protagonists – so this is new terrain.

- I’m also conscious of the fact that long descriptive passages can get dull – I will need to introduce some conflict and dialogue if this is to be more than just an exercise in a point of view.

- I’ve been thinking about how dialogue might work with a first person plural voice? In Greek tragedy the chorus spoke in unison and also call and response – I’m wondering whether I could play with that?

This extract of the start of the story is an early draft, it’s imperfect and unfinished and that makes me feel slightly vulnerable, so please forgive any rough edges and inelegance!

Tributaries

It is Christmas Eve when the house floods. We are woken by the sound of water rushing. Or perhaps it is more the feeling of it. A thing from the outside coming in. A feral presence, as if a bear or a fox is inside, and something elemental as well, picked up by the water in our veins. A cold metallic lurching.

We gather on the landing, half-visioned and gentle as cattle, somnambulant in crushed cotton, not yet believing what we sense. The noise of it, the tangible chill that rises from it.

In the toneless dawn, a damp shadow creeps up the carpeted stairs. Water licks the bottom step, the living room is an indoor pool, a brief semblance of luxury before we accept the horror.

A river runs through our home, from front door to back. Heaving, rushing in full flow. Moonlit, intent, dragging wrapped presents torn and swollen and tangles of tinsel like seaweed. Someone steps in knee deep, ice cold. Someone, frenzied, tries to salvage ruined gifts. Someone flicks on the light switch and the silver water turns yellow brown. It is rising up the walls. Our children start to cry and we retreat upstairs and rally, driven to action by adrenalin and instinct. We pack bags. We make phonecalls, to relatives and friends upland, inland, anywhere dry. We check our devices, comforted for once by their anti-nature, as if their static blue geometry can save us, deliver us swift solutions:

The river burst its banks, the flood defences failed but it is more than that, we know, because beneath our feet, beneath our Barratt Avenues, the tiny ancient tributaries, repressed and silent for so long by tarmac, brick and mortar, have found their form and smothered ours. We built on streams and floodplains. Things are now reverting. Our possessions, bobbing and mud caked are pathetic and out of place. We wait upstairs for soldiers in dinghies and neon tunics and watch three ducks and a swan swim by in the middle of our road, more at home us, and we think of people in other towns, dry towns, and the things taken for granted. Because it didn’t even cross our minds. Inland – a mile from the river, and three from the sea? No, it didn’t cross our minds.

Now we recall how we were before and how we walked to the beach, untouched, after the last storm, to look at the damage. At the water line, where the waves broke, calmly then, soft as saliva, we stepped over the domestic debris. The ring of an oven hob, a dismembered chair leg, a piece of china mug, ‘best dad’ half written, half absent, washed up on the sand, as if trying to crawl back home. We remember how we gathered around a portion of the road we had driven on only days before. The corroded yellow line still visible as a dot and dash, a lost exclamation. And how we looked up to where the houses had been, their innards from underneath, a private space exposed, pipes and wallpaper, chunks taken out like giant bite marks. We had talked about our alarm, that water could be so violent, that a liquid could be so violent in a such a physical way.

We didn’t mention our shame. That we were glad it wasn’t us.

Photo by michael.po